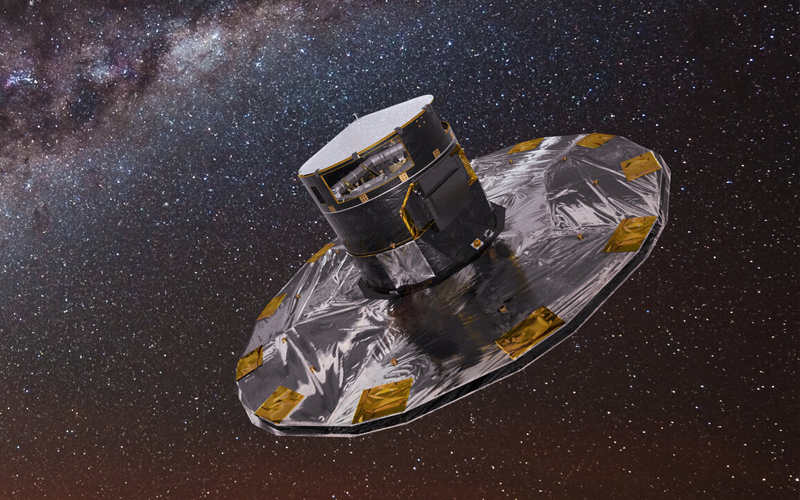

The European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft continues to collect data despite getting hit by a one-in-a-million meteoroid strike and an electronics-crippling solar storm.

Gaia was launched in December 2013 and is now stationed approximately 1.5 million kilometres away from Earth. The spacecraft was tasked with collecting data that would be used to create the most accurate map of the Milky Way to date. It was initially expected to complete a five-year mission but has continued to send valuable data back to Earth for over ten years. Its flawless record was, however, threatened in 2024 thanks to a series of unfortunate events.

Gaia is shielded to ensure it can survive micrometeoroid strikes. Like any good armour, though, there are weak spots. In April, a tiny particle smaller than a grain of sand managed to impact the spacecraft at just the right angle with enough momentum to damage Gaia’s protective cover.

While the damage from the micrometeoroid didn’t immediately threaten the spacecraft, it did allow a small amount of stray sunlight to reach Gaia’s sensitive sensors. This sunlight isn’t the sunlight that we experience on Earth, either. Its intensity is approximately one billion times that of direct sunlight felt on Earth. While teams tried to find a solution to the unwanted spotlight, another problem arose, with the sun once again taking up the role of antagonist.

Gaia’s “billion-pixel camera” employs 106 charge coupled devices (CCDs). Put simply, these little devises convert light into electrical signals for processing by the spacecraft’s onboard computer. As a testament to their reliability, all 106 CCDs have continued to work for over ten years without interruption. In May, however, one failed.

The root cause of the failure is not yet fully understood. However, at the time of the failure, Gaia just happened to have been hit by the same intense solar activity that triggered spectacular auroral events around the world. While the spacecraft is built to withstand the radiation, the levels it experienced during this period are pushing its protection to the limits.

While one of 106 CCDs doesn’t appear, at first, to be all that catastrophic, it’s worth noting that each is assigned to a unique role. The CCD that failed just happened to be vital to Gaia’s ability to confirm that it has detected a star. Without the CCD, Gaia began to register thousands of false detections that overwhelmed the system and threatened the spacecraft’s mission.

While the loss of a CCD isn’t something that can be fixed from 1.5 million kilometres away, teams working on the problem have been able to modify the threshold used by the spacecraft to identify a star. This modification has resulted in a dramatic reduction in false detections caused by both the damaged cover and the CCD failure. There is also a silver lining.

The two failures have given engineering the opportunity to refocus the optics of Gaia’s twin telescopes one final time. According to ESA, this refocusing has resulted in the spacecraft producing some of the best-quality data it has yet returned to researchers on Earth.